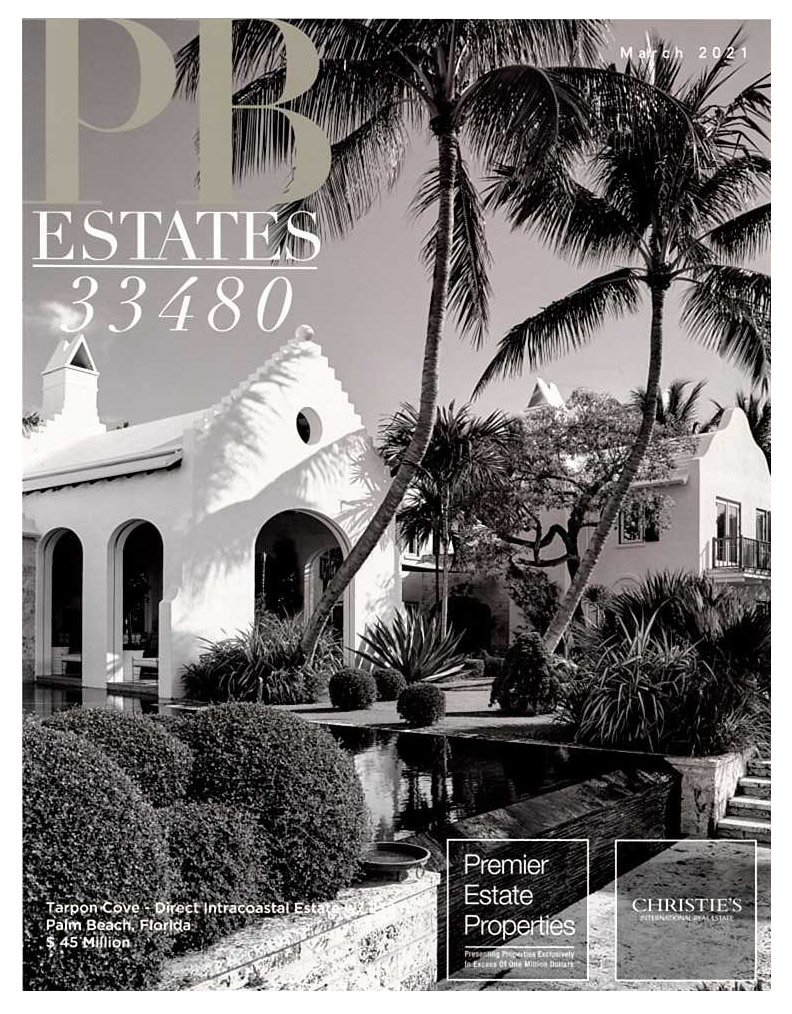

Bermuda Inspires One-of-a-kind House on Island Road in Palm Beach

By Darrell Hofheinz

Originally posted April 11, 2017 at palmbeachdailynews.com

James Berwind has long had a fondness for Bermuda’s architecture, an interest he traces to childhood vacations he spent on the south side of the island with his parents, Sandra and the late Graham Berwind.

“My parents had honeymooned on Pink Beach,” he explains, “and in the 1960s and ’70s, my family and three cousins would spend a week or 10 days there.”

So when it came time to build a house in Palm Beach, Berwind and his architect — and good friend — Tom Kirchhoff returned for inspiration to those island houses, known for their simple, rectangular forms; tall chimneys with decorative caps; and cut-stone roofs with whimsical decorative details ranging from stepped ziggurats to scalloped gables.

“I always liked the fact that the houses didn’t look intimidating. They weren’t trying to impress anyone. They always looked like a kid drew them,” says Berwind, who was trained as an environmental architect but no longer practices.

A Bermuda-style house would easily accommodate the casual, outdoor-focused lifestyle Berwind enjoys with real estate agent Kevin Clark, his partner of 10 years, and their two dogs, Scout and Brio.

The home also would be designed for entertaining. The couple champions animal-rights and pet-adoption causes, and regularly host at-home fundraisers, from small gatherings to large parties with as many as 200 guests.

The final design delivered by Kirchhoff, principal of Kirchhoff & Associates Architects, ended up meeting all those requirements for a dramatic lakefront site at 320 Island Road, the street that connects Palm Beach to Everglades Island. In all, there are 9,200 square feet of interior space, with another 1,600 square feet in the covered loggia.

On Thursday, Kirchhoff was honored with the 12th annual Elizabeth L. and John H. Schuler Award from the Preservation Foundation of Palm Beach, where Berwind serves as a trustee and Kirchhoff is a member. The annual honor recognizes new architecture that complements and builds upon the historical character of Palm Beach, according to the nonprofit foundation. Berwind and Clark also were recognized at Thursday’s award presentation.

Landscape designer Keith Williams of Nievera Williams Landscape Architecture, meanwhile, designed the grounds, which feature a gondola-style dock, terraced gardens, a stream with a waterfall and stone “outcroppings” strategically placed to appear as though the house had been built upon a foundation of coral rock.

Tarpon Cove

The property is named Tarpon Cove after the previous home on the site, a 1938 Colonial-style house owned for many years by Diana Blabon Holt, whose family had resided there for decades. She sold it to Berwind in 2012, and he initially thought he would restore it. When the house proved unsalvageable, Berwind set out to build anew — and later asked Holt if he could transfer the name. She readily agreed.

Working closely with his architect, Berwind mapped out what he wanted to build, the layout stretching over two shallow lots that front a secluded lagoon in the Intracoastal Waterway. The view punctuated by tiny Tarpon Island to the west and, beyond that, the larger Everglades Island.

“I said to Tom, this is not something I’m able to do alone or would want to do alone. But I know what I want. Tom went and red-lined what was a good idea, what was not a good idea, what code would allow, what code wouldn’t allow. And what would pass ARCOM,” he said, referring to the town’s strict Architectural Commission.

Kirchhoff, too, has long nurtured an affection for Bermudan homes, and after multiple revisions, the final design emerged. Architectural commissioner Bob Vila, who led the board as chairman when the town approved the design, said Berwind found the right architect to carry out his vision.

“Tom was a good choice, and I think he really carried it off. The lot is shallow and wide — not the best proportions — but the southern exposure and the (water) views make up for it. All in all it is one of the most exciting projects we’ve ever had in the Everglades Island area,” says Vila, who lives on the water nearby. “Unlike others in the vicinity, they got the scale right.”

Berwind and Kirchhoff both wanted the house to be true to Bermuda’s architectural traditions. To that end, the design team gathered and documented ideas on trips to Bermuda, including the island’s signature water-channeling system that funnels rainwater off buildings. From conception to occupancy, the project took more than three years.

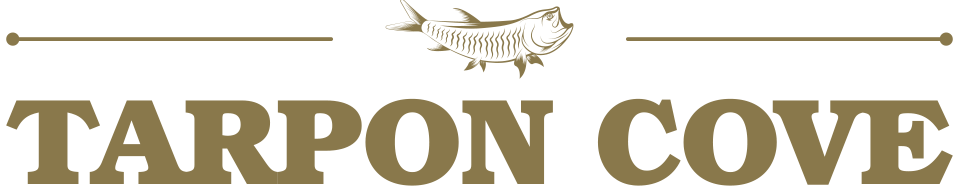

From the street, the main focus is a one-story central section that contains major public rooms. It’s patterned after traditional armament-storage buildings on the island, where British military tradition is firmly entrenched. Berwind had another key idea he wanted to express, as well: “I wanted it to look like the armament building had been added onto over the years,” he explains.

That meant building a pair of two-story structures on either side of the central section. On the west, one of those includes the family room and kitchen along with couple’s private living quarters upstairs. To the east is a detached guesthouse with four guestrooms, separated from the main residence by a garden fronting an open-air pavilion.

“The two-story ‘stacks’ are really kind of hidden. They’re off on the ends,” Berwind explains. “They’re more ‘Art Deco-y’ — what you might have seen built in the 1940s and ’50s.”

Kirchhoff takes up this theme, noting that in Bermuda, houses often begin “as modest dwellings and grow organically over time. Nothing is ever torn down or wasted, but modified to accommodate new circumstances.”

Amanda Skier, executive director of the Preservation Foundation, notes that “the rambling nature of the property … achieves the same feeling of organic development that (noted society architect) Addison Mizner strove for in each of his designs.”

Open to the Outdoors

From the foyer, one immediately looks straight through a set of glass doors to a pool with an infinity edge, its blue-black color carefully chosen by landscape designer Williams to mimic the color of the lagoon beyond it. The visual effect makes the pool and the Intracoastal Waterway appear as one.

Adjacent areas in this part of the house have banks of glass walls to capture water, loggia and garden views, and flood the interior with natural light. All of the glass can slide completely into the walls, which opens up the rooms not only to the outdoors but to each other.

When the doors are open, the public rooms and loggia, in fact, seem to blend into one expansive indoor-outdoor pavilion. And because of this arrangement — and the house’s sophisticated sound system — someone giving a presentation during a fundraiser in the living room can be easily seen and heard throughout the all of the major rooms on the first floor.

Also handy during parties is the pair of bathrooms that flank the foyer. Kirchhoff suggested them, and the arrangement recalls the arrangement — one for men, the other for women — often found in Palm Beach homes built by society architects in the 1920s and 1930s. Both bathrooms have brick-faced, barrel-vault ceilings — a nod at a old military buildings in Bermuda and at Spanish forts throughout the Caribbean.

A broad hallway leads to the west, with a simple staircase to the private quarters at the far end. The hallway is open on one side to the voluminous lakeside living room, which is crowned by a tray ceiling. Achieving the room’s height required careful planning, since it’s in the one-story portion of the house.

“We wanted to get the ceiling at the right height so it didn’t feel like the hall,” Berwind explains. “But we really had to play around with the elevation and the roofline to keep it from being too tall.”

Authentic Touches

In the same way, the house has true dormer roof windows, their characteristic shape expressed via the slanted walls in second-floor rooms.

Throughout the house can be found niches for storage and display along with built-in shelves and hidden cupboards. “I am militant about not wasting space,” Berwind says. “Why wouldn’t you use the space you have?”

Shelves in the first-floor office, for instance, were built into one of the house’s faux chimneys. Berwind explains: “On the outside of the house, it looks like a chimney. On the inside, it’s a bookshelf. Obviously, a Bermuda house would have tons of chimneys, but we didn’t need all of those fireplaces. Even in the guest house, which has gas fireplaces, the chimneys house showers. Every bit of space is used.”

Another authentic touch is a pavilion near the front of the house, built in the shape of a ziggurat-roofed “buttery,” a stable of Bermuda houses. Butteries were originally built to provide cold storage of food below ground, and today, many have been converted to studios or gazebos. Tarpon Cove’s version is just the sort of welcoming — and authentic — accent that gives the house so much charm.

For his part, Kirchhoff sums up the house as a “custom blend of authentic Bermudian architecture, modernism and old Palm Beach style.”

“The comment that we hear from people all the time is that you walk into our home and you feel welcome. You can sit down and feel like you can live here. You don’t feel like you’re in a museum,” he says. “People say that this is a house made for living. That, to me, is so gratifying.”